Taxonomy for the classification of container ports: A contribution to port governance

Taxonomía para la clasificación de los puertos de contenedores: Una contribución a la gobernabilidad del puerto

Recibido: 20/09/15 • Aprobado: 25/10/2015

Content

ABSTRACT:

For proper port management and governance, it

is necessary to understand ports not only internally or within the

context of the national port systems to which they belong but also in

terms of their role in global maritime transport networks. Because ports

are significantly dissimilar, this understanding is subject to

considerable complexity. Given this context, the present study aims to

analyse the different taxonomies in the literature for the

classification of ports, considering the main elements of these

taxonomies and their relation to the governance of the container port

logistics chain. A theoretical-empirical approach was conducted to

achieve this aim based on the literature and industry data. The analyses

indicate that the different taxonomies used to classify ports are not

comprehensive. No single model represents every port in all of its

dimensions. The existing models for classifying ports are complementary

and contribute to the analysis of port structure, functions and

governance.

Keywords: taxonomy; container ports; governance; maritime transport, literature review |

RESUMEN:

Para la gestión portuaria

adecuada y su gobernanza, es necesario entender los puertos no sólo

internamente o en el contexto de los sistemas portuarios nacionales a

las que pertenecen, sino también en términos de su papel en las redes

mundiales de transporte marítimo. Debido a que los puertos son

significativamente diferentes, este entendimiento está sujeta a una

complejidad considerable. En este contexto, el presente estudio tiene

como objetivo analizar las diferentes taxonomías en la literatura para

la clasificación de los puertos, teniendo en cuenta los principales

elementos de estas taxonomías y su relación con la gobernanza de la

cadena logística portuaria de contenedores. Se realizó un enfoque

teórico-empírica para lograr este objetivo basado en los datos de la

literatura y de la industria. Los análisis indican que las diferentes

taxonomías utilizadas para clasificar los puertos no son exhaustivas. No

hay un modelo único representa cada puerto en todas sus dimensiones.

Los modelos existentes para la clasificación de los puertos se

complementan y contribuyen al análisis de la estructura del puerto, las

funciones y la gobernabilidad.

Palabras clave: taxonomía; puertos de contenedores; gobernancia; transporte marítimo, revisión de la literatura |

1. Introduction

Given their importance as nodes between the land and the sea and their economic impact, ports are critical to the development of foreign trade and national economies. Port cargos are typically classified into three groups: i) bulk solids, ii) bulk liquid and iii) general cargo (containerised and not containerised). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2011), from 1980 to 2011, container transport (in tonnes) increased its share of the total tonnage moved through ports by 1,348% from 102 million tonnes transported in 1980 to 1.48 billion in 2011. In addition to this increase in recent decades, containerised cargo is an important component of port operations because of the higher added value and the stricter service requirements associated with this cargo type and the increased complexity of the container port logistics chain.Currently, ports in general and particularly those ports that specialise in containerised cargo face unprecedented challenges in an environment of increasing competition and pressure from different stakeholders with respect to making ports drivers of economic growth (Chang, Lee and Tongzon, 2008).

Today, the major container carriers compete globally for cargo that is handled by shippers who also operate globally, which requires a global network of maritime container transport. The shippers are required to combine resources and distribute products worldwide. Shipping operations must provide global coverage (i.e., access to major global trade routes), high service frequency and reduced transit times. Costs must be low and service must be of the highest quality (Lirn, Thanopoulou and Beresford, 2003). In this context, ports are pressured by severe inter-port competition and challenged by the high negotiating power of the global alliances. To increase or at least maintain its position in the market, a port must respond satisfactorily to the various requirements of the maritime transport lines and adapt to a changing environment (Chang et al., 2008).

This context justifies the increasing importance of port governance and the need to analyse the environment in which the ports are located. In an environmental analysis, one can distinguish internal and external environments, and the external environment can be subdivided into structural and remote environments (Yoshihara, 1976).

In the case of ports, the internal environment should be understood as not only referring to the port itself but also the context of the cluster (De Langen, 2004), or the port logistic chain (López and Poole, 1998), i.e., the set of actors or groups that have an interest in or are affected by port activities (Winkelmans, 2008) and activities related to the arrival of ships and the cargo located in the port area (De Langen, 2004). Because port performance is a function of the interaction between the various actors of the port logistics chain, one should consider the activities within a port from a logistics perspective (Cooper, 1994; Bichou and Gray, 2004). That is, port operations include the activities associated with inland port-related logistics (pre-port), maritime activities related to the port (post-port) and the activities that occur within the port (Haezendonck, 2001). Therefore, the activities within a port are related to a number of other activities whose reach exceeds the spatial limits of the port, from the cargo's origin (export), through the port and to the destination (import). Because 'the external environment' refers to the port system of the country in which the port is located, the model of port management and ownership in a given region has special relevance.

Bichou and Gray (2004) discussed the evaluation of port performance from a logistics perspective. They argued that the essence of logistics and supply chain management concerns the integration of different processes and functions within a firm but also extends to a wide network of organisations with the ultimate goal of cost reduction and customer satisfaction. Against this background, the remote port environment can be defined as the global maritime transport networks in which the ports are located.

However, according to Bichou and Gray (2004), few studies in the port literature discuss ports in the context of logistics and supply chains and many adopt a fragmented approach to port operations. There is a lack of studies that discuss ports from a broader perspective that considers not only the port or the national port system but also (and in particular) the port's position (current and potential) in the global maritime transport networks.

Thus, the present article aims to analyse the different taxonomies in the literature for the classification of ports, considering their main components and their relationship with the governance of port logistics chains. The specific aims are as follows: i) to review the existing literature on the classification of ports, ii) study the factors considered in each classification, evaluating redundancy, differences and similarities, iii) propose a taxonomy for port governance based on the preceding aims and iv) analyse the relationship between the different elements of the proposed taxonomy and the governance of port logistics chains.

2. Port classification: literature review

According to Bichou and Gray (2005), ports are dynamic and complex organisations, often distinct from one another, where various activities are performed by and for different actors. There are several models in the literature for the classification of ports. However, according to Bichou and Gray (2005), given the dissimilarity of the models, there is no single classification applicable to all port types. Thus, the existing classifications only partially encompass the range of ports and the adequacy of the classification depends on the subject of study. The most widespread approaches classify ports according to i) a port's degree of development or the generation to which a port belongs, ii) a port's ownership and management model and iii) a port's inclusion in the global maritime transport networks.According to Bichou and Gray (2005), a substantial portion of the existing literature on the roles and functions of ports is published by governmental and international agencies, such as the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD), the World Bank, UNCTAD and the International Association of Ports and Harbours (IAPH). UNCTAD's series of monographs on port management in collaboration with the IAPH, which extends over two decades, is particularly notable (Bichou and Gray, 2005). However, there are also a few academic studies on the subject. Significant contributions include Branch (1986), Frankel (1987), Goss (1990), Alderton (1999) and Robinson (2002).

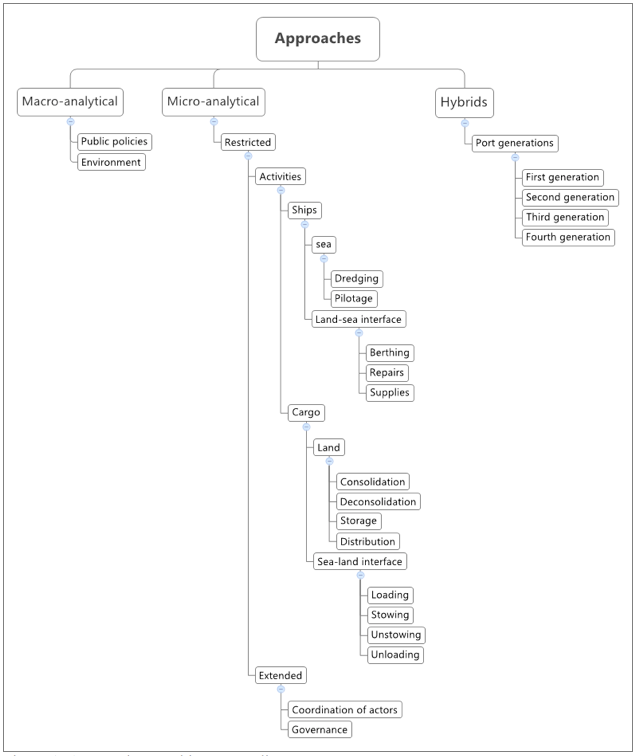

Bichou and Gray (2005) classify these studies according to three approaches: i) macro-analytical, which includes political, geographical (spatial and urban), economic and social perspectives; ii) micro-analytical, which addresses the activities, operations and functional dimensions of ports; and iii) hybrid, which combines elements of the first two approaches.

Figure 1: Approaches used in port studies

In the macro-analytical approach, two topics have primary importance:

public policy, in which the ports are viewed as catalysts of economic

development that generate socio-economic benefits for the regions in

which they are located, and environmental protection, i.e., port

planning and management should consider sustainable development

(Wakeman, 1999 as cited in Bichou and Gray, 2005). Regarding the second

topic, there is a series of studies on the impact of port activities.

These studies employ various approaches and analytical methods and have

identified a number of contentious issues for economists, planners,

politicians and environmentalists.In the micro-analytical view, restricted approaches to and extended definitions of ports are considered. Restricted approaches consider ports simply as facilities for the maintenance of ships and the transfer of cargo and passengers (MARAD, 1999 as cited in Bichou and Gray, 2005). In addition to the traditional topics of the handling, storage and modal interchange of goods, extended definitions include a wide range of business activities related to maritime commerce, such as the definition from European Seaports Organisation (ESPO, 2004 as cited in Bichou and Gray, 2005). This second approach also addresses questions related to the coordination of actors and the governance of the port cluster in addition to the purely functional or operational aspects of ports.

Typically, port activities are divided into two types, cargo-related and ship-related (UNCTAD, 1999), because ships and cargo form the two main components of any port system. Ship services include services provided at sea or in inland waterways (such as dredging and pilotage) and services provided at the land-sea interface (such as berthing, ship repair and the supply of water and fuel). Bichou and Gray (2005) divide cargo services into services provided at the ship-shore interface (stowing, loading and unloading) and services executed exclusively on land (cargo consolidation and deconsolidation, storage and distribution).

With respect to these services, according to Bichou and Gray (2005), there is occasionally confusion regarding the actual client (the ship or the cargo) because certain port activities serve both and are performed by secondary actors, such as customs or health authorities, logistics operators or inland container depots. Therefore, in-port activities are related to a set of other activities whose reach extends beyond the port's spatial limits and which are referred to as the 'port logistics chain'. The governance of the different actors involved in this chain (De Langen, 2004), promoted by the port authority, can improve a port's efficiency (De Langen, Nijdam and van der Horst, 2007).

The third approach (hybrid) combines elements from the micro- and macro-analytical perspectives on the roles and functions of ports. According to Bichou and Gray (2005), an important aspect of this approach is the classification of the different port generations proposed by UNCTAD, which is widely cited in the literature. This classification is presented in the next section.

2.1. Ports according to generation

First-generation ports only perform traditional port activities; i.e., they are simply interfaces between the land and the sea. Second-generation ports are characterised as support service centres for transport, industry and trade that provide certain value-added cargo services, such as labelling volumes, consolidation, deconsolidation and completing production processes. Third-generation ports are dynamic links in international trade networks and active agents that design and implement strategies for the complete development of a port's area of influence. According to Bichou and Gray (2005), technology and know-how are determining factors for this type of port, particularly the intensive use of information technology (IT) to manage port logistics.

According to Paixão and Marlow (2003), a third-generation port is sufficient for a relatively predictable economic scenario. However, the authors argue that in a changing market, ports should adopt a new logistic approach: agility, which characterises fourth-generation ports. In addition, the authors propose a method to implement the idea of agile ports based on the concept of agile production (Gunasekaran, 1999). Table 1 summarises the main characteristics and identifying elements of each port generation.

Table 1: Characterisation of ports according to generation

| Generation | Main characteristic | Identifying elements |

| First | Limited to traditional port activities | Loading and unloading ships Handling goods Storage |

| Second | Value-added activities | Consolidating and deconsolidating cargo Packing and marking packages Completing production |

| Third | Dynamic links of international trade networks | Strategies for obtaining cargo (hinterland) Strategies for attracting shipping lines (vorland) Port marketing developed Intensive use of information technology |

| Fourth | Agility | Lean management in the port Flexibility Just-in-time techniques Process redesign |

2.2 Models of port ownership and management

Although 'port functions' and the 'port activities' are substantially similar, the concept of 'port' is highly variable (Bichou and Gray, 2005). According to Bichou and Gray, a port can be a stowing company, a terminal operator, a public authority, a private company or even a cluster of different actors and operators. Given this complex context, the literature reports different models of ownership and management that are applicable to ports.According to Thomas (1994), the many ports around the world have developed in different ways under a combination of economic, political, geographical, social, cultural and military influences and without a universal standard of port ownership.

As for the possible forms of port ownership, Beth (1985) (cited in Bichou and Gray, 2005) separates ports into those controlled by the state, local administrations and private companies. Similarly, although in greater detail, Alderton (1999) classifies ports into state-owned, autonomous, municipal and private.

The model of state ownership is found in countries such as France, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece. In these countries, the port authorities are state organisations that have their own legal status and financial independence. The major decisions are made by the state, which significantly influences port management.

The municipal model is found in ports in Germany, Holland and Belgium, such as the ports of Rotterdam, Hamburg, Bremen and Ghent. In this model, although the ports are administered by municipalities, because their management is subject to a number of regulations, they are also controlled by the federal and state governments.

According to Bichou and Gray (2005), the World Bank identifies three types of port asset: basic infrastructure, operational infrastructure and superstructure. In municipal ports, the infrastructure is responsibility of the municipality except where the national interest, and therefore federal financing, is involved. In addition, the municipal model may include national advisory bodies that aim to coordinate the port system.

The autonomous model, in which the ports are managed by state governments, somewhat resembles the municipal model. This model is found in the United States, where states manage the ports through port authorities, agencies or state departments (Fawcett, 2007). However, because of ports' influence over the local economic activities in geographically larger U.S. states, certain municipalities seek to create and manage port authorities. Such arrangement would be a case of municipal ownership and therefore, U.S. port system represents a hybrid model. On the other hand, the same phenomenon does not occur in smaller states due to administrative efficiency matters.

The private model is found in Anglo-Saxon ports. In this case, there is total autonomy. That is, the government does not participate in port management and the port is administered solely by the private sector. Depending on the regulatory framework and existing controls, this ownership model risks becoming a private monopoly.

Regarding the involvement of the public and private sectors in ports, Cullinane and Song (2002) proposed the following taxonomy: i) a public port, ii) a public/private port with a dominant public sector, iii) a private/public port with a dominant private sector and iv) a private port. Another widely known taxonomy is that of the World Bank (2001), which describes four port management models according to a port's speciality: i) a service port, ii) a tool port, iii) a landlord port and iv) a private service port. These models are described below and vary depending on the orientation of the port (local, regional or global), the service provider (public, private or both), the superstructure ownership and who provides the port's workforce.

The service port model ispredominantly public and in it the port authority owns the land and all of the assets (fixed and mobile) and is responsible by all the port functions. The cargo is handled by personnel directly affiliated with the port authority. Normally, this type of port is controlled by the federal government's department responsible for transportation. In this model, a single body is responsible for management and operations, the performance of regulatory functions, infrastructure and superstructure development and other operational activities.

The model's primary strength is that the responsibility is centred on a single entity, which favours cohesion. However, the lack of internal competition can result in inefficient administration, insufficient innovation and services not oriented to the user and the market.

The tool port model is characterised by the division of operational activities. The port authority owns, develops and maintains the infrastructure and superstructure of the port. The equipment owned by the port authority is operated by the port authority's employees, whereas other berth and yard operations are operated by private companies, typically small-scale operators (Bichou and Gray, 2005).

According to Bichou and Gray, this model's strength is the avoidance of investment duplication because the facilities are provided by the public sector. Weaknesses include the fragmented responsibility for cargo handling, which can create conflicts between the small-scale operators or between them and the port administration, the risk of under-capitalised investment and barriers to the development of strong private operators.

According to Bichou and Gray (2005), in the landlord port model, the public port authority retains ownership and leases the port terminals to private operators. The maintenance of the basic port infrastructure, such as road access, navigation channels, maritime signalling and berths, is responsibility of the port authority, whereas private operators purchase and install their own equipment (superstructure) and may also be responsible for the operational infrastructure.

Bichou and Gray (2005) argue that this model's strength is that the company that owns and maintains the equipment is the same one that operates the equipment, which facilitates planning and adaptation to market conditions. However, expansion attempts by more than one private operator can generate overcapacity. Additionally, there may be a duplication of efforts to promote the port between the terminal operators and the port authority, and efforts to coordinate marketing and planning actions are required.

The fourth model, known as a private serviceport, is one in which the public sector is absent from port activities and the private sector is responsible for port management and operations. This management model corresponds exclusively to the private ownership model (Bichou and Gray, 2005).

According to Bichou and Gray, this model's strength is its orientation toward the market. The model's main weakness is associated with the risk of monopolistic behaviour, particularly if there is no significant inter-port competition.

The characteristics of each port management model are summarised in Table 2 according to the following elements: i) asset ownership, both infrastructure and superstructure - public or private, ii) port administration - public or private, iii) port operations - public or private, iv) the degree of intra-port competition - absent, low, medium or high and v) difficulties in coordinating port activities - low, medium or high.

Table 2: Summary of port management models

| Element | Service port | Tool port | Landlord port | Private service port | |

| Assets | Infrastructure | Public | Public | Public | Private |

| Superstructure | Public | Public | Private | Private | |

| Administration | Public | Public | Public | Private | |

| Operation | Public | Pub./Priv. | Private | Private | |

| Intra-port competition | Non-existent | Low | High | Non-existent | |

| Difficulty of coordinating port activities | Low | Medium | High | Low | |

Table 3: Possible combinations of ownership and management port models

| Port owner |

Service port

|

Tool port

|

Landlord port

|

Private service port

|

| Federal/State |

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

| State/Autonomous |

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

| Municipal |

X

|

X

|

X

|

|

| Private |

X

|

Tongzon and Heng (2005) studied the relationship between privatisation and port efficiency and noted that private sector participation in the port sector is helpful for increasing operational efficiency. However, the full privatisation of ports is not effective in increasing operational efficiency, as indicated by a nonlinear relationship between operational efficiency and port privatisation. Additionally, the study revealed that the most appropriate degree of privatisation for ports and container terminals is between the public/private and completely private modes, which suggests that port authorities should limit private-sector participation in ports (Tongzon and Heng, 2005). Bichou and Gray (2005) identified variations in the terminology used to characterise the port management models. However, according to them, the concept of port authority is used in all of the different models and can be characterised as landlord; port operator or port developer, although the classification may generate controversy.

Another taxonomy for classifying ports considers the role played by ports in the global maritime transport networks. This taxonomy is presented in the following section.

2.3 Port classification according to position in the global maritime transport system

From the early 1990s, the major maritime shipping companies active in the regular-line transport of containerised cargo began to increase the ship size and concentrate routes. This strategy is associated with the hub-and-spoke idea, the primary objective of which is to increase the economies of scale by operating larger vessels, thus lowering unit costs per transported container while maintaining local flexibility from the spokes. By concentrating the destinations to a few ports and decreasing the number of stops, a ship spends more time at sea and less time in port for loading and unloading, which increases revenue and improves the dilution of fixed costs. To facilitate this mode of operation, the selected concentrator port must efficiently handle large volumes of containers to meet customer expectations. Additionally, the connection with the spokes is essential because the connection creates revenue by feeding the hub and generating cargo movement (containers shipped and delivered).Based on this concept, a complex network of worldwide maritime transport was developed using hub and feeder services (Aversa et al., 2005).

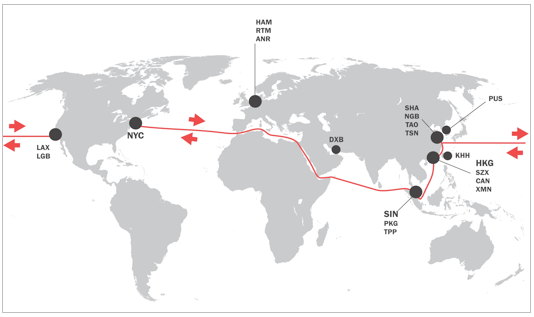

Because of the use of hub-and-spoke systems, the main shipping routes are concentrated along the east-west axis (Figure 2). The routes connect the markets of Europe, Asia and North America with emphasis on the transpacific route in the Far East-to-North America direction (transpacific eastbound) and the North America-to-the Far East (transpacific westbound) and the Far East-to-Europe routes. This arrangement reflects China's position as the main global supplier and the consumer potential of the North American and European markets. These primary routes (main services) are connected to secondary routes (feeder services) in the south-north and north-south directions.

Figure 2: Primary maritime container routes

The concentration of cargo transportation along the east-west axis is

also suggested by the ranking of the 20 largest ports according to the

number of twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) moved in 2010. The ports

with the highest movement of containers are positioned along this axis,

particularly the Asian ports and above all the Chinese. Among the ten

largest ports in the world in TEUs handled in 2010, six are Chinese and

only one is outside Asia (Rotterdam).Regarding the world merchant fleet and the concentration in the industry, according to Alphaliner data (2011), the percentage of the fleet operated by the ten largest maritime container carriers increased from 50% in 2000 to 60% in 2010, whereas the capacity (in TEUs) of the fleet operated by these companies more than tripled in the same period from just over 2.5 million in 2000 to nearly 8 million in 2010.

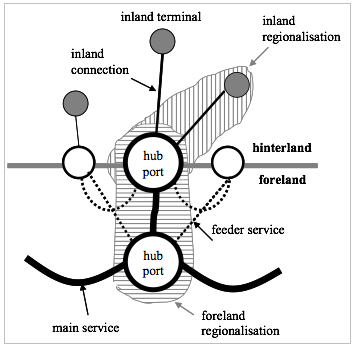

Because of the widespread use of the hub-and-spokesystem, substantial attention has been focused on what characterises a hub port and the conditions that are required to configure this kind of port. The hub idea was initially established by Taaffe, Morrill and Gould (1963), who identified the process by which many small ports throughout the world form a network with one or two major global ports and numerous smaller ports to create an integrated transport system (Taaffe et al., 1963 as cited in Bichou and Gray, 2005). According to Campbell (1994), hubs are transhipment facilities and act as links between multiple origins and destinations.

According to Bichou and Gray (2005), aspects such as geographical location, captive cargo volumes, intermodal links, feeder service networks, infrastructure and rates are often considered to be the most important factors for a port to acquire hub status. These factors refer not only to transhipment and but also the hinterland, vorland and umland capacities.

'Hinterland' refers to the area 'behind the port', i.e., the port's potential to generate cargo or the port's area of influence (Muñoz, 1989). According to Rodrigue and Notteboom (2010), although there is no consensus among geographers regarding the meaning of hinterland, the term has been defined since its first appearance in the literature as a set of sites linked to a port via cargo flows. With increasing inter-port competition, hinterlands have ceased to be specific to each port and become common to several ports (Peyrelongue, 1999; Hilling and Hoyle, 1984 as cited in Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2010), which makes the term's delimitation more difficult.

According to Rodrigue and Notteboom (2010), 'vorland' ('foreland' in English) was established by Weigend (1958) and refers to the area 'in front of the port', or the port's area of maritime influence, which is determined by the connectivity between the port and the maritime routes. In short, the term refers to the greater or lesser proximity of the port to the main shipping routes (Muñoz, 1989).

The umland, according to Valpuesta and Manzano (2001), comprises the area of the port's immediate influence (the port area) and its area of primary influence (the area where the port's presence is essential and whose development depends largely on the port activities). Therefore, 'umland' refers to the port itself and the surrounding area and includes the infrastructure and those elements with a direct impact on the level of the port logistics service (e.g., the efficiency and effectiveness of services and their prices). The umland connects the hinterland and the vorland.

Considering the context of containerised cargo and inter-modality, it is perceived a strong inter-dependence between hinterland and vorland port areas (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2010). The awareness of this interdependence has generated in recent decades studies that consider instead of the traditional separation of hinterland, vorland and umland the logistic chain in a broader sense as an opportunity to increase efficiency and decrease costs. For example, transcending the hub-and-spoke idea, Notteboom and Rodrigue (2005) established the concept of port regionalisation, which refers to i) a network of inland terminals to facilitate cargo consolidation and deconsolidation and increase efficiency while eliminating bottlenecks associated with congestion and a lack of physical space (inland regionalisation) and ii) a network of several ports that belong to the same operator or with some type of relationship (foreland regionalisation). The concentration of ship calls and the regionalisation of ports are evidence of the significant changes that the port system has undergone in recent decades (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2010). The relationship between these factors is schematically presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Hub-and-spoke system and port regionalisation

Source: adapted from Rodrigue and Notteboom (2010).

To return to the topic of port classification according to the port's

position in the global maritime transport network, according to De

Langen, van der Lugt and Joost (2002), several researchers have sought

to refine the initial hub concept of Taaffe, Morrill and Gould (1963).

Hayuth (1981) established the load centre idea, which was improved by

Notteboom (1997) using the following criteria to define 'load centre':

i) a port with regular international transport activities, ii) a large

container volume, iii) a large number of transhipments and iv)

considerable growth in the port's market share. For Notteboom, to be

considered a load centre, a port should fulfil at least three of the

criteria. Finally, De Monie (1997) developed a typology based on four

major groups of ports according to their geographic location, area of

influence, intermodal access network and the services provided (Table

4).Source: adapted from Rodrigue and Notteboom (2010).

Table 4: Classification of container ports according to their position in the global maritime transport network

| Classification | Characteristics |

Global pivots

|

- Located on the major maritime transport routes

- Large cargo volume- Accommodate the largest ships - High service frequency

- High percentage of transhipments

|

Load centres

|

- Located on the periphery of major global maritime transport routes

- Large cargo volume- Small percentage of transhipments - Large number of intermodal links to facilitate the transit of goods

- Accommodate large-capacity ships

|

Regional ports

|

- Serve large urban agglomerations but have no importance within the international maritime network

- Can perform a large number of transhipments or assume load centre functions - Accommodate medium-capacity ships

- Intermediate service frequency

|

Minor ports

|

- Serve a local base

- Practically no transhipments- The moved goods originate or are destined for locations close to the port base

- Accommodate small ships often without a regular schedule

|

Source: adapted from De Monie (1997).

The status achieved by a specific port in the proposed classification

by De Monie (1997) fundamentally depends on the characteristics of the

port and the selection criteria considered by port customers. Typically,

a port has two different types of customers: the maritime companies or

ship owners that call at the port and the exporters, importers and

freight forwarders. The interaction among these customers defines the

flow of goods and directly influences port activity. Among these actors,

shipping companies deserve special attention because the users of the

second group tend to choose a port depending on the ships that call

there. Furthermore, whereas a specialised container port accommodates a

large number of exporters, importers and freight forwarders, the number

of shipping lines that call at each terminal is often quite limited

because regular-line maritime transport is a capital intensive and

highly concentrated business, as discussed above. According to Chang et

al. (2008), the operational decisions regarding the route and the

frequency of calls are often made by the liner carriers, who try to

maximise income based on shipping and port costs and estimates of demand

for the ports of origin and destination. Additionally, based on the

existing routes and the frequency of calls (defined by the liner

carriers) and in consideration of criteria such as cost, operational

efficiency and added services, users of the second group select their

preferred ports. Thus, the increasing bargaining power that results from

the concentration in the maritime sector of containerised cargo -

global alliances between maritime shipping companies - exacerbates the

competition between ports (Chang et al., 2008).Several studies that evaluate the criteria of port selection can be found in the literature. The number of such studies has grown since the 1990s and includes Murphy, Daley and Dalemberg (1992), Murphy and Daley (1994), Tongzon (2002/2009) and Tran (2011) contributions. Based on a general analysis of such studies, one can identify the main criteria for port selection from the perspective of the ocean carriers and the exporters, importers and freight forwarders. From the standpoint of the carriers, the important criteria are the port's cargo-generating potential, the location and the distance from the main shipping routes (main services), the capacity to accommodate large ships (particularly with respect to hull size), the efficiency in loading and unloading operations, the anchorage waiting times and charges. From the perspective of the exporters, importers and freight forwarders, the important factors include port costs, land freight connections to the port or from the port to the destination, the number and the coverage of regular-line services, maritime freight, the ship frequency and maritime and door-to-door transit times. All of these criteria are associated with the previously described ideas of hinterland, vorland and umland.

In the sections on data analysis in these studies, attention is focused on multivariate procedures (multiple regression, factorial analysis and conjoint analysis) (Hair Jr. et al., 1998; Malhotra and Birks, 2007), multi-criteria studies based on the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and the logic developed by Saaty (1990) or adaptations thereof and the fuzzy logic (Magala and Sammons, 2008).

3. Reference structure for the study of port governance

According to Geiger (2010), a governance model must answer three basic questions: Who governs? What is governed? How is it governed? The answers to these questions define the structure, elements and actions of governance. In addition to these three questions, a fourth preliminary question can be formulated (Why is it governed?), which is linked to the governance outcomes.The classification of ports in the literature primarily contributes to the understanding of port governance structure because most studies discuss 'models of ownership and port management', which are mistakenly referred to in the literature as 'governance models'. This approach is a misconception because a governance model does not only include the governance structure but should also include other aspects (the activities, the elements and the governance outcomes). Moreover, there appear to be significant gaps in these models with regard to these other aspects.

The idea of channels (logistics, trade and supply) of Bichou and Gray (2005) aids the analysis of the elements of governance. However, this approach neglects issues such as the architecture of the port logistics chain and the actors who belong to this chain, which should be considered elements of a governance model. The classification of ports according to their position in the global maritime transport network by De Monie (1997) is a contributory factor. However, this classification is insufficient for the analysis of the governance outcomes. Furthermore, in addition to the position of ports in the global maritime transport networks, metrics related to the efficiency, the effectiveness and the cost of port logistics activities should be considered.

No in-depth study on governance actions was found in the international literature. Governance actions, which are implemented on the governance elements and conditioned by the governance structure, are important because they can enhance the governance outcomes, that is, the efficiency and the effectiveness of the port logistics chain and the port's insertion into the global maritime transport network.

Thus, based on the analysis of different taxonomies from the literature for the classification of ports and the identification of the main research gaps, a framework can be proposed for analysing the governance in container port logistic chains (Table 5).

Table 5: Framework for analysis of governance in port logistics chains

| Questions | Dimensions | Variables |

| Why the port is governed? | Governance outcomes | Port efficiency |

| Port effectiveness | ||

| Insertion in the global maritime transport network | ||

| Who governs? | Governance structure | Port ownership model |

| Port management model | ||

| Framework for the coordination of actors and port logistics flows | ||

| How the port is governed? | Governance actions | Coordination actions for actors in the port logistics chain |

| Coordination actions for port logistics flows | ||

| What is governed? | Governance elements | Actors in the port logistics chain |

| Port logistics flows |

4. Conclusions

The combination of the various existing models of port classification is useful for allowing a broader knowledge of port logistics chain. This knowledge, in turn, is critical to the development of comprehensive and consistent port governance model, allowing answering the key questions related to port governance (Why the port must be governed? Who will govern the port? What dimensions and elements must be considered? and How these elements must be managed in order to achieve a better port governance?).

Therefore, the combination of the different taxonomies for port governance presented in this study may contribute to the development of this expanded sense of the port logistics chain. This understanding will support the development of a port governance model, in order to coordinate the different actors involved in a port logistics chain and improve the port logistics processes.

References

Alderton, P. M. (1999). Port Management and Operations. London: Lloyds of London Press.Alphaliner (2011). Volumes hit high. Alphaliner Weekly Newsletter, 14, 1-12.

Aversa, R., Botter, R. C., Haralambides, H. E. and Yoshizaki, H. T. Y. (2005). A mixed integer programming model on the location of a hub port in the east coast of South America. Maritime Economics & Logistics, 7, 1-18. doi:10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100121

Beth, A. (1985). General Aspect of Port Management. Port Management Textbook. Bremen: Institute of Shipping Economics and Logistics.

Bichou, K. and Gray, R. (2005). A critical review of conventional terminology for classifying seaports. Transportation Research Part A, 39, 75-92. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2004.11.003

Bichou, K. and Gray, R. (2004). A logistics and supply chain management approach to port performance measurement. Maritime Policy and Management, 31, 47-67. doi: 10.1080/0308883032000174454

Branch, A. E. (1986). Elements of Port Operation and Management. London: Chapman and Hall.

Campbell, J. F. (1994). Integer programming formulations of discrete hub location problems. European Journal of Operational Research, 72, 387-405. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(94)90318-2

Chang, Y. T., Lee, S. Y. and Tongzon, J. L. (2008). Port selection factors by shipping lines: different perspectives between trunk liners and feeder service providers. Marine Policy, 32, 877-885. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2008.01.003

Cooper, J. (1994). The global logistics challenge: logistics and distribution planning. London: Ed. James Cooper.

Cullinane, K. and Song, D. W. (2002). Port privatisation policy and practice. Transport Reviews, 22, 55-75. doi: 10.1080/01441640110042138

De Langen, P. W. (2004). Governance in seaport clusters. Journal of Maritime Economics and Logistics, v. 6, n. 4, 141-156. doi:10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100100

De Langen, P. W., Nijdam, M. N. and van der Horst, M. R. (2007). New indicators to measure port performance. Journal of Maritime Research, 4 (1), 23-36. Retrieved from http://www.jmr.unican.es/ES/index.htm

De Langen, P. W., van der Lugt, L. M. and Joost, H. A. (2002, November). A stylised container port hierarchy: a theoretical and empirical exploration. Paper presented at International Association of Maritime Economists Conference- IAME 2002, Panama City. Retrieved from http://www.cepal.org/usi/perfil/iame_papers/proceedings/Langen_et_al.doc.

De Monie, G. (1997, June). The global economy, very large containerships and the funding of mega hubs. Port Finance Conference, London.

Fawcett, J. A. (2007). Port Governance and Privatization in the United States. Research in Transportation Economics, 17, 207-235. doi: 10.1016/S0739-8859(06)17010-9

Frankel, E. G. (1987). Port Planning and Development. New York, NY: John Wiley.

Goss, R. (1990). Economic policies and seaports: the diversity of port policies. Maritime Policy and Management, 17, 221–234. doi:10.1080/03088839000000028

Gunasekaran, A. (1999). Agile manufacturing: a framework for research and development. International Journal of Production Economics, 62, doi: 10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00222-9

Haezendonck, E. (2001). Essays for strategy analysis for seaports. Leuven: Garant.

Hair Jr., J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. and Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hayuth, Y. (1981). Containerisation and the load centre concept. Economic Geography, 57, 160-176.

Hilling, D. and Hoyle, B. S. (1984). Spatial approaches to port development. In: B. S. Hoyle and D. Hilling (Eds.), Seaport systems and spatial change (pp. 1-19). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Lirn, T. C.; Thanopoulou, H. A. and Beresford, A. K. C. (2003). Transhipment port selection and decision-making behaviour: analysing the Taiwanese case. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 6, 229-244. doi: 10.1080/13675560310001626990

López, R. C. and Poole, N. (1998). Quality assurance in the maritime port logistics chain: the case of Valencia, Spain. Supply Chain Management, 3, 33-44. doi: 10.1108/13598549810200915

Llaquet, J. L. E. (2007). Mejora de la competitividad de un puerto por medio de un nuevo modelo de gestión de la estrategia aplicando el cuadro de mando integral. [Improving the competitiveness of a port through a new management model that applies the Balanced Scorecard]. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. E. T. S. de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos.

Magala, M. and Sammons, A. (2008). A New Approach to Port Choice Modelling. Maritime Economics and Logistics, 10, 9–34. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.mel.9100189

Malhotra, N. K. and Birks, D. F. (2007). Marketing Research: an applied approach (3rd ed). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Muñoz, J. M. B. (1989). El Puerto de la Bahía de Cádiz: sus áreas de influencia (The Port of the Bay of Cadiz: their areas of influence) Cuadernos de Geografía, 1, 35-54. Retrieved from http://rodin.uca.es:8081/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10498/14091/18387330.pdf?sequence=1.

Murphy, P. R. and Daley, J. M. (1994). A Comparative Analysis of Port Selection Factors. Transportation Journal, 34 (1), 15-21.

Murphy, P. R.; Daley, J. M. and Dalemberg, D. R. (1992). Port Selection Criteria: An Application of a Transportation Research Framework. Transportation Research Part-E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 28, 237-255.

Notteboom, T. H. (1997). Concentration and the load center development in the European container port system. Journal of Transport Geography, 5, 99-115. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6923(96)00073-7

Notteboom, T. H. and Rodrigue, J. P. (2005). Port regionalization: towards a new phase in port development. Maritime Policy and Management, 32, 297–313. doi: 10.1080/03088830500139885

Paixão, A. C. and Marlow, P. B. (2003). Fourth generation ports – a question of agility? International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 33, 355-376. doi: 10.1108/09600030310478810

Peyrelongue, C. M. (1999). El puerto y la vinculación entre lo local y lo global [The port and the link between the local and the global]. Revista Eure, 25 (75), 103-120. doi: 10.4067/S0250-71611999007500005

Robinson, R. Ports as elements in value-driven chain systems: the new paradigm. (2002). Maritime Policy and Management, 29, 241-255. doi: 10.1080/03088830210132623

Rodrigue, J. P. and Notteboom, T. (2010). Foreland-based regionalization: Integrating intermediate hubs with port hinterlands. Research in Transportation Economics, 27, p. 19-29. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2009.12.004.

Saaty, T. L. (1990). How to Make a Decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process. European Journal of Operational Research, 48, 9-26. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(90)90057-I

Thomas, B. (1994). The need for organisational change in seaports. Marine Policy, 18, 69-78. doi: 10.1016/0308-597X(94)90090-6

Tongzon, J. and Heng, W. (2005). Port privatization, efficiency and competitiveness: Some empirical evidence from container ports (terminals). Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 39, 405-424. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2005.02.001

Tongzon, J. L. (2009). Port choice and freight forwarders. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 45, 186-195. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2008.02.004

Tongzon, J. (2002, November). Port Choice in a Competitive Environment. Paper presented at International Association of Maritime Economists Conference- IAME 2002, Panama City. Retrieved from http://www.cepal.org/usi/perfil/iame_papers/proceedings/Tongzon.doc.

Tran, N. K. (2011). Studying port selection on liner routes: an approach from logistics perspective. Research in Transportation Economics, 32, 39-53. doi: 10.1016/j.retrec.2011.06.005

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development - UNCTAD (1999). The Fourth Generation Port. UNCTAD Ports Newsletter, 19, 9-12. Retrieved from http://www.unescap.org/ttdw/Publications/TIS_pubs/pub_2484/pub_2484_fulltext.pdf.

Valpuesta, L. L. and Manzano, J. I. C. (2010). Análisis de la actividad económica del puerto de Sevilla y su influencia provincial. Serie Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, 55, Universidad de Sevilla.

Winkelmans, W. (2008, January). Port Governance and Stakeholder Relations Management. One day conference on current trends and practices in the organisation, operation and management of ports and port terminals. Institute of Transport and Maritime Management Antwerp, University of Antwerp. Greece, 2008. Retrieved from http://hermes.civil.auth.gr/pgtransport/docs/Winkelmans_PORT_GOVERNANCE_and_SRM_2008.pdf.

World Bank (2001). Alternative port management structures and ownership models. World Bank Port Reform Tool Kit, Module 3, pp. 1-77. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPRAL/Resources/338897-1117197012403/mod3.pdf.

Yoshihara, H. (1976). Towards a comprehensive concept of strategic adaptive behaviour of firms. In: H. I. Ansoff, R. P. Declerck, R. P. and R. L. Hayes. (Eds.), From Strategic Planning to Strategic Management (pp. 103-124). London: Wiley.

1. Universidade de Caxias do Sul (UCS), Brasil – Email: gbbvieir@ucs.br

2. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Brasil – kliemann@producao.ufrgs.br

2. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Brasil – kliemann@producao.ufrgs.br

No comments:

Post a Comment